Auteurs et autrices / Interview de Ted Rall (VO)

Ted Rall kindly accepted to share his thoughts on the importance of Central Asia on the international scene and the way America handles freedom of speech and international politics. (Read the french version here)

Hi Ted, tell us a bit about yourself.

Hi Ted, tell us a bit about yourself.

I'm 44 and a member of Generation X—a group of Americans sandwiched between the huge and influential age cohort born between World War II and the assassination of President Kennedy, and their children. I grew up in a typical suburb in Ohio, in the part of the Midwest called the Rust Belt because so many 19th and 20th century industries were rotting away.

When I was two years old, my parents separated. They were divorced when I was five, in 1968. My parents' divorce was a seminal event in my life. My father was financially well-off, but I lived with my mother, a schoolteacher who struggled to pay the bills. I saw then that one's fortune in life—their class, education, even health—depends on random chance. That realization formed the basis of my political development. Unlike many Americans, who buy into a Protestant work ethic which is implicitly judgemental of the poor and downtrodden, I look at a homeless person and think to myself, "there but for slightly different luck lies I."

My father was an aeronautical engineer and, I think it's fair to say, a cold fish. I never connected to him emotionally. I only saw him on weekends, for six hours, because the family court ordered the visits. I don't know why he wanted to see me; he seemed bored. My mom was my parent. She is brilliant, insecure, high-strung and a real firecracker. She's 73 years old, and when she visits me she runs me ragged all day until I collapse from exhaustion.

My mom was born in France in 1935. She was born in the Landes, in the southwest of the country near the Pyrenees Mountains. But her family was Breton, an ethnically distinct group that was oppressed by the French central government. When she was five, the Nazis invaded. Like most French people under the Occupation, she witnessed terrible things and suffered deprivation. When I look into her eyes it amazes me to think that those irises saw Wehrmacht and SS troops.

She taught me to distrust authority, to read between the lines, to check things out for myself rather than to believe what I was told. As a teenager and even now, my rebelliousness caused her a lot of heartache. "It's your fault," I tell her sometimes. "You made me this way!"

I published my first editorial cartoon in the Kettering-Oakwood Times, a small biweekly newspaper that served my hometown, in 1979. I was 16 years old. I was paid $15, about what a paper that size would pay now for a cartoon by a professional syndicated cartoonist. By the time I went to college, I had eight small newspapers in my portfolio.

I went to Columbia University on a full scholarship, to study engineering. It was great. It was the peak of the punk and New Wave music movements, and I haunted many nightclubs and cool record shops. I was also politically active. I checked out the Communist, Libertarian and Socialist parties before finally working for mainstream Democratic political candidates. I majored in applied physics and nuclear engineering because my parents told me it would be easier to find work after I graduated. (They were probably wrong.) Yes, I know how to make a nuclear weapon. Saddam Hussein would have loved to have met me. A year after I arrived, though, President Ronald Reagan radically slashed the federal budget. College financial aid virtually disappeared overnight. Thousands of students, no longer able to afford tuition, dropped out. I held out as long as I could, working long hours—sometimes more than a full-time job.

I went to Columbia University on a full scholarship, to study engineering. It was great. It was the peak of the punk and New Wave music movements, and I haunted many nightclubs and cool record shops. I was also politically active. I checked out the Communist, Libertarian and Socialist parties before finally working for mainstream Democratic political candidates. I majored in applied physics and nuclear engineering because my parents told me it would be easier to find work after I graduated. (They were probably wrong.) Yes, I know how to make a nuclear weapon. Saddam Hussein would have loved to have met me. A year after I arrived, though, President Ronald Reagan radically slashed the federal budget. College financial aid virtually disappeared overnight. Thousands of students, no longer able to afford tuition, dropped out. I held out as long as I could, working long hours—sometimes more than a full-time job.

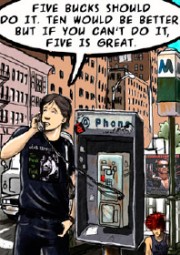

I drove a taxi, worked as a longshoreman on the crumbling docks of lower Manhattan, tutored rich children in mathematics and calculus, and stole office equipment and fenced it. Anything to earn money to pay the tuition.

In the end, it was too hard. I was working too much so I couldn't study enough. Besides, I couldn't earn the money I needed to pay the room, board and fees. It all fell apart after three years, one year short of a degree. I ended up on the streets of Manhattan, broke and homeless. It took over a year to crawl back to some measure of solvency, culminating with moving into my own apartment. It was in the slums and we got broke into all the time and we ultimately got evicted because we couldn't pay the rent on my salary (I was a junior trader at Bear Stearns, the brokerage firm that collapsed recently). I'm writing about my experience after college in a graphic novel, "The Year of Loving Dangerously." Pablo J. Callejo, the cartoonist who drew "Bluesman," is doing the artwork.

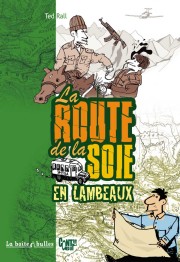

Your book “Silk Road to Ruin” is about to be published in France, and arguably represents one of the most thorough and up-to-date account of the situation in Central Asia. How and when was this project born? Where does your strong interest in Central Asia come from?

Your book “Silk Road to Ruin” is about to be published in France, and arguably represents one of the most thorough and up-to-date account of the situation in Central Asia. How and when was this project born? Where does your strong interest in Central Asia come from?

Thank you for saying that. I was trying to be thorough. Central Asia is the most interesting and, from a Western foreign policy and economic perspective, the most important part of the world for the foreseeable future—even more so than the Middle East. Anyone should be able to pick up and read "Silk Road to Ruin" and find out why it matters so much. You don't need any background whatsoever. I assume that the average reader comes to the subject cold, and tell him or her what they need to know.

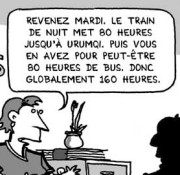

In the fall of 2001, The Village Voice and the Los Angeles radio station where I did talk radio (like other liberal commentators I lost my job after Bush took over) sent me to Afghanistan to cover the American invasion. It was a thrilling but harrowing experience. Three of the 45 reporters in my convoy were killed. Others were seriously injured. My wife and I literally fled for our lives. We raced for the northern border with Tajikistan, knowing that if we didn't make it out before it got dark we would be murdered.

When I got back, my publisher Terry Nantier, at NBM Publishing, called to see how I was doing. He insisted that I write a book about my experience, both in graphic novel/comics form and in prose. To understand Afghanistan, I thought and still believe, one has to see the country in its full regional context. It's both a Central Asian nation and part of South Asia. The war was at least partly motivated by the U.S. interest in oil and oil pipelines, an issue that affects the surrounding countries known as the "Stans": Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Pakistan.

Then I started work on the book I'd really wanted to write. I'm grateful that NBM took a chance on this project, especially since the American press has had absolutely zero interest in reviewing the book. One of the biggest newspapers in the country, a very influential daily, told us that they thought Central Asia was "too hard" of a subject for Americans to understand, even as the subject of a book review! But Americans aren't as stupid as their media assumes. People bought and sought out the book on their own.

Why Central Asia and not, say, the tropical beaches of Thailand? I've always been a contrarian. If a public figure is unpopular or even reviled, I want to know more about them. If a topic is obscure and ignored, I check it out—like my mom taught me.

Speaking of my mom, she bought me a subscription to National Geographic magazine when I was a teenager. I devoured it every month, but no more so than the month—I wish I still had the issue, but it was during the late 1970s—when they did a feature about what was then the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, part of the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan, the writer said, was the most rugged and remote place on earth. Leafing through the photos of the vast steppe with snow-capped mountains along the horizon as I sat in my mother's backyard in southwest Ohio, I thought, wow, I'll never get to go there.

I was wrong. In 1997 I was a writer for P.O.V., a magazine for adventure-seeking guys. My editor agreed to send me on a crazy assignment: drive the ancient Silk Road from Beijing to Istanbul through the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. It took six weeks and cost 44 pounds from my diarrhoea-ravaged frame. I thought to myself, "I got that out of my system! Never again."

I was wrong. In 1997 I was a writer for P.O.V., a magazine for adventure-seeking guys. My editor agreed to send me on a crazy assignment: drive the ancient Silk Road from Beijing to Istanbul through the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. It took six weeks and cost 44 pounds from my diarrhoea-ravaged frame. I thought to myself, "I got that out of my system! Never again."

But I'd fallen in love with the region. I went back in 1999, twice in 2000, 2001, 2002, last year…you get the idea.

Page 174 your character cries in despair: “why do I keep coming back here?” Indeed what is it about central Asia that makes you repeatedly brave the blazing heat, severe diarrhoea and deadly militia? The natural beauty and wilderness of the place? Its importance on the international scene?

Page 174 your character cries in despair: “why do I keep coming back here?” Indeed what is it about central Asia that makes you repeatedly brave the blazing heat, severe diarrhoea and deadly militia? The natural beauty and wilderness of the place? Its importance on the international scene?

All of the above. Although to be honest, I like to challenge myself, to take myself out of, as Americans say, my comfort zone. The harsh elements—Central Asia has the world's highest mountains, hottest deserts and most frequent severe earthquakes—and unstable politics—the place is constantly roiled by rebellions, insurgent attacks, brutal dictatorships and border wars—are part of the appeal to anyone who prides himself on his ability to extract himself from difficult situations. It helps that the people are fascinating and generous and hilarious, and that there's always something to write about that Americans and other Westerners really ought to know about before, say, the next 9/11.

You depict many traumatic moments in your book… but what is your personal “favourite”? The one story that you would tell your friends or colleagues back home?

You depict many traumatic moments in your book… but what is your personal “favourite”? The one story that you would tell your friends or colleagues back home?

Probably talking my way out of being executed by the Taliban. My friend and I were pulled off a bus in Pakistani Kashmir and informed that we had five minutes to settle up with God before they shot us. I saw my fellow passengers staring at us—none of them were foolish enough to carry American passports—and thought to myself: How weird. They're going to see us die. Then the bus will drive off, they'll go home to their families. We'll be the poor bastards, the punchline of the worst possible joke, in a random story. You'll never believe this! Check out what happened to me…

Fortunately for me, one of our would-be executioners had attended New York University during the early 1980s. We bonded over New York and what to look for (physically) in a woman.

But you should still buy the book. There's lots more, including a piece about the worst natural disaster in history—which hasn't happened. Yet.

Many of your claims and accusations are backed by precise facts that must have been difficult to gather. How do you do your research?

Many of your claims and accusations are backed by precise facts that must have been difficult to gather. How do you do your research?

There are great sources of reliable information and journalism about Central Asia online. EurasiaNet.org and Asia Times (atimes.com) are major sources for me. There are also academic papers. Also, the British media—especially the BBC and Reuters—commit a lot of resources to covering the Stans.

The problem is, a lot of stories vanish from online archives within a month, or even after a few days. My trick is to check for new stories frequently and save them.

You are often described as a “political cartoonist”. What do you think it is about cartoons that makes them so popular in depicting political issues? Do you read cartoons/comics yourself?

You are often described as a “political cartoonist”. What do you think it is about cartoons that makes them so popular in depicting political issues? Do you read cartoons/comics yourself?

Ironically, political cartoons are in danger of disappearing entirely from U.S. newspapers and magazines. Cowardly editors removed them after the 9/11 attacks, or replaced hard-hitting (i.e., relevant) cartoons with bland, unopinionated pabulum. But readers love them. It's weird to see a medium everyone loves vanish. It's as if TV networks around the world refused to air soccer.

Political cartoons rock because you don't need any qualifications to draw them. You don't have to go to art school. It's a totally populist medium. Kids making fun of their teachers by drawing them on their notebooks are political cartoonists. They're snotty, unfair, maddeningly simple and—at their best—expose hypocrites and empty suits with ruthless efficiency.

I try not to read too many political cartoons because I worry that they'll influence me. What if I read a cartoon, "forget" about it, then come with an idea I think is mine but really belongs to someone else? It would be mortifying. But I have a day job as an editor for major syndicate, United Media. I have to look at comics, especially daily comic strips, for my work.

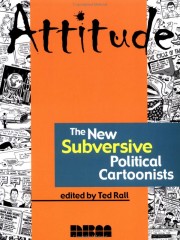

My favourite cartoons are those that appear in the alternative weekly newspapers like The Voice and SF Weekly. I compiled interviews with some of my favourite artists, along with examples of their work in a book called "Attitude: The New Subversive Political Cartoonists." There are two sequels to "Attitude," about humorous and web-based cartoons.

My favourite cartoons are those that appear in the alternative weekly newspapers like The Voice and SF Weekly. I compiled interviews with some of my favourite artists, along with examples of their work in a book called "Attitude: The New Subversive Political Cartoonists." There are two sequels to "Attitude," about humorous and web-based cartoons.

Your taste for criticizing America seems to go as far back as your high-school thesis, which was about “American plans to occupy France as an enemy power at the end of World War II”. Do you consider yourself antipatriotic? Or simply actively involved/interested in your country’s affairs and politics?

Your taste for criticizing America seems to go as far back as your high-school thesis, which was about “American plans to occupy France as an enemy power at the end of World War II”. Do you consider yourself antipatriotic? Or simply actively involved/interested in your country’s affairs and politics?

A person who doesn't do everything he can to pressure his country to live up to its ideals, and be the best country that it can be, is no patriot. He is an idiot. He is, at best, a knee-jerk nationalist, a fascist, scum.

The United States has amazing founding principles and high-flying rhetoric. Theoretically at least, the U.S. is dedicated to equality, justice and freedom for everyone. The reality, it is obvious to anyone who reads history or cracks open a newspaper, is quite different. I suppose that it's possible to justify the gaping chasm between lofty ideals and gutter tactics like propping up dictators and torture. Lord knows people do it all the time. I think it's disgusting and a betrayal the people who died founding and fighting for this nation, at least those who thought they were giving their lives for those noble ideas.

In high school Americans are taught that we should revere those, like Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, who stood up for what was right despite enduring insults and abuse. I took those civics classes seriously.

The severity of some of your accusations and the fact that you are still free and alive to talk about them is a tribute to our freedom of speech… But have you ever had to suffer from your political stand? Have you ever been intimidated, insulted or received threats?

The severity of some of your accusations and the fact that you are still free and alive to talk about them is a tribute to our freedom of speech… But have you ever had to suffer from your political stand? Have you ever been intimidated, insulted or received threats?

The worst annoyances have been economic. Before 9/11 and the post-9/11 era of neo-McCarthyism during which anyone to the left was smeared as anti-patriotic (things are better but not yet back to pre-9/11 norms), I was the most widely reprinted cartoonist in The New York Times. They haven't used me once since. I was in Time and Fortune magazines. They fired me. I've lost half my client list, half my income. It's all because, after 9/11, I refused to join my wimpier peers by doing cartoons comparing Bush to Churchill and depicting Saddam in SS gear. I vowed to remain the same cartoonist, as relentless and critical of the government under the Bush regime as I was under Clinton. I've paid a price for that decision. So has my family.

But I wouldn't change a thing. No one will ever remember how much I earned. They'll remember how I acted.

Of course I've received hundreds of threats of death and dismemberment. The climate was unbelievably vicious in 2002 and 2003, during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq.

Right-wingers were brazen. My Caller ID revealed one of the callers, who threatened to slit my throat, to be a New York police official. He left his full name and phone number on my voicemail. On one occasion, firefighters came to my apartment building and tried to break down the door. It got so bad that I had to leave my building through the back alley.

Of course I've received hundreds of threats of death and dismemberment. The climate was unbelievably vicious in 2002 and 2003, during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq.

Right-wingers were brazen. My Caller ID revealed one of the callers, who threatened to slit my throat, to be a New York police official. He left his full name and phone number on my voicemail. On one occasion, firefighters came to my apartment building and tried to break down the door. It got so bad that I had to leave my building through the back alley.

Fortunately the anger has cooled somewhat, and the right has seen all of their projects go sour. So they're feeling a bit gun-shy. But they'll be back at it as soon as the politicians in Washington give them permission again.

Although I didn't like those particular pieces, I sympathize with the cartoonists who drew the Danish Mohammad cartoons. What's funny is that, here in the U.S., right-wingers vigorously defended their right to draw them—the very same people who, like 1996 and 2000 Republican presidential candidate Alan Keyes, called for me to be shot and imprisoned as an enemy combatant. Freedom is for foreigners, not Americans.

Nowadays all I have to worry about is the government spying on me. My phone company confirmed that they're listening to my phone calls. They know I'm not a terrorist. They want me to know that they're violating my privacy rights. It's a form of harassment.

Am I right in saying that you have French origins? Has this worsened your position during the earlier days of the Iraq crisis when France and America were in complete disagreement?

Am I right in saying that you have French origins? Has this worsened your position during the earlier days of the Iraq crisis when France and America were in complete disagreement?

As I said above, yes, my mother is French. I have dual citizenship; I hold U.S. and French passports. I feel badly for the second- and third-generation immigrants who live in France but can't get citizenship, but I plan to retire in France when I'm older, so it's convenient.

There have been a few attacks on me based on my French origins, but not many. Mainly this is because I have been a loud defender of France here in the States, writing several columns pointing out that losing a war (as in 1940) isn't the same as not fighting it. Very few Americans understand that more soldiers died in six weeks in France in May-June 1940 than the U.S. lost during all of Vietnam. And Vietnam was a traumatic experience, one that this country has never been able to move past. History is a great tool for shutting up fools.

I would like to think that your publications have an impact in opening people’s eyes to the world of international politics. They have surely opened mine. Do you receive much feedback from “enlightened” readers?

I would like to think that your publications have an impact in opening people’s eyes to the world of international politics. They have surely opened mine. Do you receive much feedback from “enlightened” readers?

Yes, definitely! I love my readers. You can see how smart and fun and cool they are by reading the comments section of my blog, at www.rall.com. I definitely hear from people who say I've prompted them to dig further into a topic or even changed their point of view. Every now and then a Republican writes me to say he or she has moved left because of my writing, but that's rare. It's incredibly gratifying if even one person reconsiders their position or the way they live their lives because of something you wrote or drew.

Americans are more interested in international politics than they get credit for. Or, more accurately, many Americans are. When I had my radio show in L.A., I started a segment called "Stan Watch: Breaking News from Central Asia," with minutiae from Central Asia, including the weather! It was conceived as a joke, as commentary on the "fact" that people don't care about news from Canada, much less Uzbekistan. But it became wildly popular. It got picked up by NPR and the BBC. "Stan Watch" was a hit! People followed the developments surrounding an assassination attempt against Uzbek President Islam Karimov the way others track sports. Americans would read and watch international news if it were offered to them. But it's not. Consider what happened with Al Jazeera English. It's banned here. No one can see it, unless they stream it on the Internet, and that's very difficult and awkward.

The U.S. has the best rock music and the best burgers in the world, but we don't have a free press.

You seem to know a thing or two about politics, so tell me, are we in trouble with our new French president Nicolas Sarkozy? He seems very pally with George W. Bush… (…who, and please tell me if I am wrong, you don’t seem to admire that much:))

You seem to know a thing or two about politics, so tell me, are we in trouble with our new French president Nicolas Sarkozy? He seems very pally with George W. Bush… (…who, and please tell me if I am wrong, you don’t seem to admire that much:))

I don't understand what the French were thinking. Did they really need their own version of Bush's poodle now that Tony Blair is out of politics? Were they really so spooked by the riots in the suburbs? (Part one of a solution: anyone born in France ought to be granted French citizenship.) Was Ségolène really so terrible? Honestly, there's something wrong with a guy who marries a woman three months after he meets her.

Now that Americans are feeling sane—Bush's approval rating is 27 percent—they're entitled to look down on the French. Finally. Where this leaves me, as both French and American, I don't know. Confused, mainly.

What are your current and future projects? Any more trips to Central Asia?

What are your current and future projects? Any more trips to Central Asia?

I mentioned "The Year of Loving Dangerously." If that graphic novel sells well, I'd like to make it part two of a trilogy. Next would be the sequel, "The Year of Chris." I'm thinking of writing a political manifesto for Americans wondering what we should do next, as well as a straightforward fiction graphic novel that parodies the media.

I have been getting the travel bug. I'd love to cross into Tibet over land to get the real scoop—not the official tour accompanied by government minders—about what's going on there.

Thanks a lot Ted!

Thanks a lot Ted!

You're welcome, and thanks for doing this. I'm always amazed that anyone cares what I think!

Site réalisé avec CodeIgniter, jQuery, Bootstrap, fancyBox, Open Iconic, typeahead.js, Google Charts, Google Maps, echo

Copyright © 2001 - 2024 BDTheque | Contact | Les cookies sur le site | Les stats du site